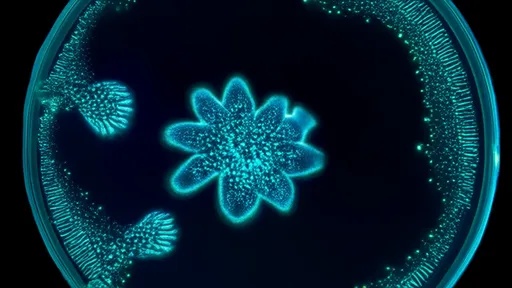

The unlikeliest of urban planners now sits in petri dishes rather than skyscrapers. Physarum polycephalum, a brainless, single-celled organism that creeps along forest floors as a pulsating yellow mass, has become an unexpected muse for transportation engineers and city designers. This primitive slime mold, often found decomposing leaf litter in cool damp forests, possesses an uncanny ability to create highly efficient networks that rival human-engineered infrastructure.

When researchers at Hokkaido University first placed oat flakes in a pattern mimicking Tokyo's urban centers and let the slime mold loose in 2010, they witnessed something remarkable. The organism extended tendrils that gradually formed an interconnected network strikingly similar to Tokyo's existing rail system. The mold hadn't simply copied human design - it had independently arrived at comparable solutions through its own biological optimization processes.

Nature's Algorithm Versus Human Calculation

The slime mold's approach to network formation represents a radically different paradigm from traditional urban planning. Human engineers typically work top-down, starting with major routes and filling in connections. Physarum, by contrast, explores its environment in all directions simultaneously, then reinforces the most efficient pathways while allowing redundant connections to atrophy. This creates networks that balance efficiency with resilience - if one pathway gets blocked, alternatives already exist.

Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki, one of the pioneers in this field, explains: "The mold doesn't 'think' in our sense, but through simple feedback mechanisms - where nutrients are present, the plasmodium grows; where they're absent, it retracts. What emerges is a solution optimized for both resource distribution and fault tolerance." These properties have made slime mold models particularly attractive for designing transportation systems that must withstand disruptions from accidents to extreme weather events.

From Laboratory Curiosity to Planning Tool

What began as biological curiosity has evolved into serious urban research. Teams across Europe and North America have begun applying slime mold algorithms to real-world planning challenges. In 2019, British researchers used mold simulations to propose modifications to Manchester's bus network that could reduce transfer times by 17% while maintaining the same coverage. The German Aerospace Center has experimented with mold-inspired designs for emergency evacuation routes in stadiums and theaters.

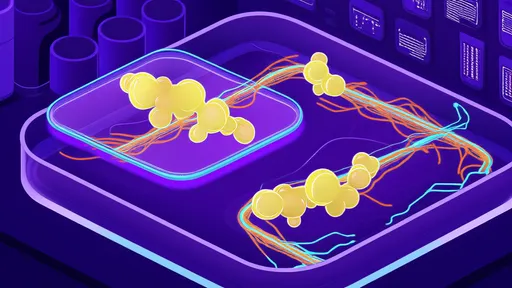

The process typically involves creating a nutrient landscape where cities are represented by food sources (often agar plates with oat flakes standing in for population centers), then allowing the mold to grow under controlled conditions. Advanced algorithms then translate the biological patterns into transport models. Surprisingly, these models frequently identify corridors that human planners overlook, particularly in rapidly growing cities where development has outpaced infrastructure planning.

Challenges and Limitations of Biomimicry

While promising, slime mold urbanism isn't a panacea. Biological solutions sometimes conflict with political, economic or social realities. A mold might "solve" a city's traffic by suggesting a highway through a historic district or protected wetland. Moreover, human transportation serves purposes beyond efficiency - roads symbolize connections between communities, public transit affects property values, and infrastructure projects create jobs.

There's also the matter of scale. Slime molds excel at connecting dozens of points, but modern megacities contain thousands. Researchers are developing computational models that can scale up the organism's principles while incorporating human constraints. The most valuable applications may come in rapidly urbanizing areas of the developing world, where planners face the daunting task of designing entire transit networks from scratch under tight budgets.

The Future of Living Infrastructure

Some visionaries imagine going beyond mere simulation. Experimental architect Rachel Armstrong proposes creating "living cities" where modified slime molds or similar organisms actually form part of the urban infrastructure - perhaps as self-repairing transit guides or adaptive traffic control systems. While such proposals remain speculative, they underscore how radically biomimicry could transform urban spaces.

As climate change and population growth strain traditional planning approaches, cities may increasingly turn to nature for solutions. The humble slime mold, having perfected network design over millions of years of evolution, offers insights that could make future cities more efficient, resilient and perhaps even more organic in their functioning. In an era seeking sustainable solutions, sometimes the best ideas come from the most unexpected places - even from primordial ooze creeping across a petri dish.

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025