In the quiet corners of our homes, an invisible war rages on. Unseen by the naked eye, microbial colonies battle for dominance on every surface—from kitchen counters to forgotten leftovers. What was once the domain of laboratories has now become a fascinating DIY science experiment: observing microbial warfare through homemade petri dishes.

The concept is simple yet profound. By creating nutrient-rich agar plates using household items, amateur scientists can cultivate microorganisms from their environment. Within days, intricate ecosystems emerge as bacteria and fungi compete for resources. Some colonies form alliances; others engage in chemical warfare by secreting antibiotics. The results are both beautiful and terrifying—a microscopic Game of Thrones playing out on your dining table.

Dr. Eleanor Shaw, a microbiologist who began her career culturing soil samples in her childhood bedroom, explains why this phenomenon captivates both scientists and laypeople. "Microbial competition is the original arms race," she says. "These organisms have been perfecting chemical warfare for billions of years—long before humans discovered penicillin." Her popular YouTube series documenting kitchen counter microbes has garnered millions of views, proving public fascination with this hidden world.

Creating these microbial battlefields requires surprisingly accessible materials. A basic agar solution can be made from beef broth and gelatin, though more sophisticated hobbyists use agar-agar powder for clearer observation. Sterilization remains crucial—boiling containers and working near a flame prevents contamination from unwanted species. The real magic begins when swabs from different household surfaces are streaked across the plates. Toothbrushes, smartphone screens, and even belly button lint become sources of microbial diversity.

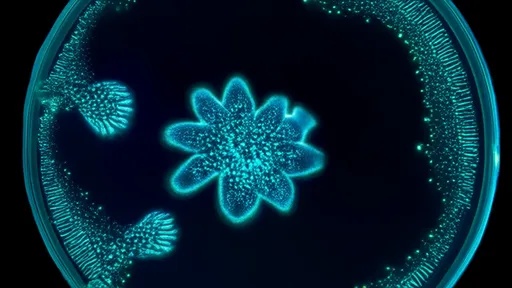

Within 48 hours, the drama unfolds. Milky Staphylococcus colonies might form defensive barriers against spreading Penicillium molds. Vibrant Serratia marcescens (known for its blood-red pigmentation) could chemically suppress competing strains. Advanced enthusiasts sometimes introduce "challenge organisms" like baker's yeast to observe specialized predation. The most striking interactions often occur at colony borders where antibiotic production creates visible inhibition zones—clear moats in the agar where no competitor dares grow.

Beyond their entertainment value, these kitchen experiments provide genuine scientific insights. Citizen science projects have documented antibiotic-resistant strains emerging in domestic environments. A 2022 study published in Frontiers in Microbiology analyzed over 3,000 homemade petri dishes and identified previously unknown antimicrobial compounds produced by common kitchen molds. "The average home contains microbial diversity rivaling tropical forests," notes lead researcher Dr. Rajiv Mehta. "We're just beginning to understand this pharmacopoeia beneath our sinks."

Ethical considerations accompany this growing hobby. While most household microbes pose little danger, some enthusiasts have accidentally cultured pathogens like MRSA or Aspergillus. Responsible practitioners wear gloves, seal plates with parafilm, and sterilize used materials in pressure cookers. The International Society of Amateur Microbiologists has established safety guidelines emphasizing disposal protocols and discouraging attempts to culture bodily fluids.

For educators, microbial gardening offers unparalleled teaching opportunities. High school biology teacher Marcus Yang replaced his textbook bacterial transformation labs with a semester-long "kitchen wars" project. "Students become invested when they culture microbes from their own environments," he observes. "They'll voluntarily design experiments testing whether probiotics defeat mold, or if smartphone UV cleaners actually work. That's authentic scientific curiosity."

The artistic community has also embraced this phenomenon. Bioartist Zara Patel creates living portraits by "painting" with multicolored microbial strains. Her exhibition "Domestic Wars" featured time-lapse videos of bacterial colonies forming intricate patterns reminiscent of cellular automata. "We're conditioned to see microbes as enemies," she reflects. "But watching their self-organizing battles reveals an alien beauty—a reminder that conflict shapes all life."

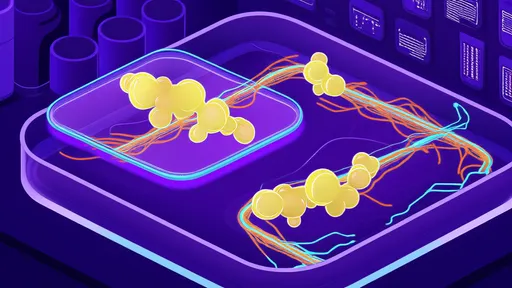

As the hobby grows, so does its technological sophistication. DIY incubators made from reptile heaters maintain optimal temperatures. Raspberry Pi cameras document colony expansion hourly. Online forums buzz with techniques for staining specific metabolites or constructing anaerobic chambers from mason jars. Some enthusiasts even experiment with CRISPR-modified strains (though most academic microbiologists caution against amateur genetic engineering).

Perhaps the greatest revelation from these microbial gladiator arenas is humility. That white spot on your week-old yogurt isn't just mold—it's a triumphant survivor that outcompeted billions of rivals. The pink film in your shower? A biofilm fortress engineered by extremophiles. As we peer into these miniature ecosystems, we're reminded that our homes belong to countless unseen inhabitants engaged in eternal struggle. Their chemical warfare invented our medicines; their competition drives evolution. In culturing these microscopic battles, we don't just observe nature—we become part of it.

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025

By /Jul 14, 2025